State of the Proving Infrastructure Landscape - 2024Q4

Optimistic is dead, long live ZK

Interested in earning rewards by running nodes? You can sign up to Rent a Node to begin today. If you’re a project interested in renting ZK compute, start now with credits.

TL;DR

In our report for Q4 of 2024, we explore the ongoing prover decentralization efforts in the L2 space, as well as recent project launches in the proving infra landscape. In addition, we will dive into the topic of economic security in the context of ZK proof generation from different angles, covering 1. the parallels between Bitcoin mining and proof mining, 2. economic security through staking and restaking, and 3. viable alternatives to promote accessibility, security, and decentralization.

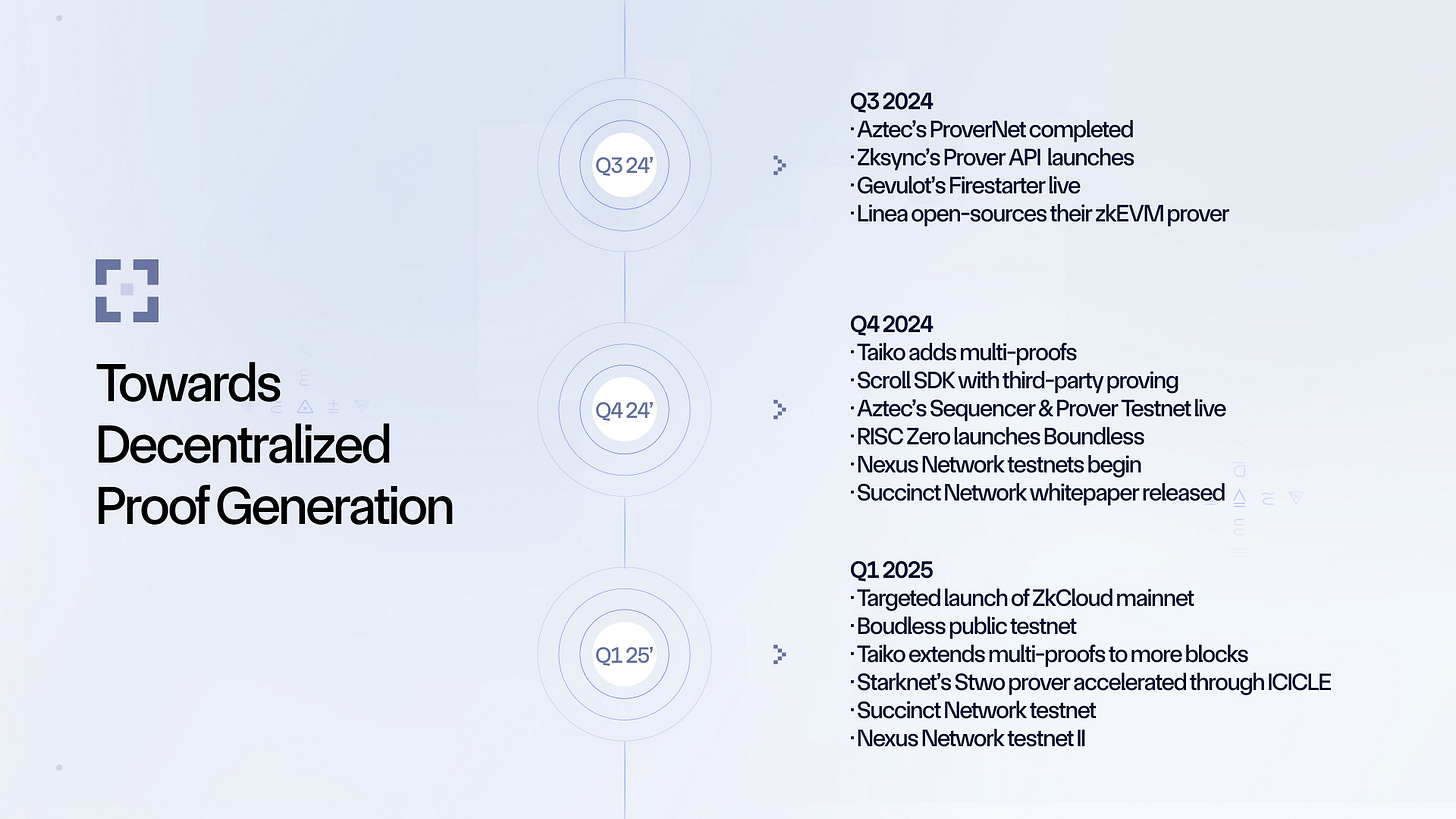

Recap of Q3 2024

In our Q3 report, we discussed a significant shift in the proving infrastructure landscape, as the industry moved from theory and plans to practical advancements. This included two notable initiatives in prover decentralization: Aztec's ProverNet contest and the launch of ZKsync Era’s Prover API.

In Q3 we also saw several notable launches, including RISC Zero unveiling Boundless, Fermah emerging from stealth with an AVS-based prover network, Cysic Network introducing its testnet, Polyhedra launching Proof Cloud in partnership with Google Cloud, and Gevulot onboarding prover node operators to its scalable production-ready network Firestarter.

We discussed an important industry-wide collaboration that took shape in September: the formation of the ZkBoost Consortium, which brought together 42 leading companies to develop a standardized API for proof generation. This initiative represents a crucial step toward reducing technical overhead and fragmentation in the proving landscape.

In addition, we analyzed the most common workload allocation mechanisms - such as auctions, order book-based systems, proof racing, stake-based lotteries, and random selection -, with emphasis on how they impact decentralization, and revealing the trade-offs they may come with.

Now let’s look at how the proving landscape evolved in Q4.

New developments and prover decentralization among validity and ZK-rollups

Taiko’s multi-proofs

In early November, Taiko reached a significant milestone by integrating zero-knowledge (ZK) proofs into its rollup, advancing its multi-proof architecture to enhance security and scalability. This multi-proof strategy enables Taiko to mitigate risks associated with any single proof system by supporting different proof types across multiple tiers.

*Source: https://taiko.mirror.xyz/4c6VNhjKLHOMaNKRryyKHkiHcWx7caRax_mC0jTr-sY

Previously, Taiko relied solely on Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) to prove blocks. The ZK-proof integration requires 3% of all blocks to be validity-proven, with plans to increase this coverage to 10-25% by March 2025 and ultimately transition into a full-fledged validity rollup until the end of the year. By combining TEEs with ZK proofs, Taiko is creating a comprehensive security model in the L2 space.

Scroll announces its rollup stack, the Scroll SDK

Scroll unveiled its rollup stack, the Scroll SDK, a production-ready framework for deploying sovereign blockchain networks using its zkEVM technology. The Scroll SDK standardizes zkEVM chain deployment, providing developers with a customizable toolkit to configure and deploy their own L2 chains.

The proving pipeline of the Scroll zkEVM includes three types of proofs: chunk proofs for block validation, batch proofs for EIP-4844 blob data availability, and bundle proofs that aggregate multiple batches for finalization.

*Source: https://scroll.io/blog/proof-recursion-scrolls-darwin-upgrade

Networks built on the Scroll SDK can enable third-party proof generation to source validity proofs: Proof outsourcing is already available with ZkCloud built by Gevulot, Sindri, and Snarkify.

Aztec launches Sequencer & Prover Testnet

After launching Provernet 1.0 in September, the very first network to test decentralized proof generation and real-time proof outsourcing, Aztec announced and launched its Sequencer & Prover Testnet (S&P Testnet) in Q4.

In the S&P Testnet, provers generate proofs for entire epochs instead of blocks. An epoch consists of 32 consecutive slots. As per the epoch proving guide, there are two kinds of proofs in Aztec:

Client proofs use the ClientIVC proving system and are generated on user devices such as mobile phones or in browsers when users initiate transactions.

Server-side proofs are generated by third-party proof providers. These are Honk proofs, the generation of which includes three main parts:

Transaction proving: If transactions include public functions, the Aztec Virtual Machine and Public Kernel circuits are run to prove the correct execution. The client proofs are then verified and converted into a Honk proof by running the Tube circuit.

Rollup proving: the side effects from every individual transaction are then used as the input to the rollup circuits, and aggregated through a tree-like structure, via the Base, Merge, and Root Rollup circuits, with the final root rollup proof being verified on L1.

Parity circuits: These circuits are used for cross-chain messaging only, and their output is fed into the block root rollup circuit.

*Source: https://hackmd.io/@aztec-network/epoch-proving-integration-guide

As a privacy-preserving protocol, Aztec Network is looking to launch with a decentralized set of sequencers and provers from day 1, and the launch of the Sequencer & Prover Testnet is a crucial step towards testing sequencer selection, sequencer and prover coordination and the governance mechanism.

Developments in the proving infra landscape

The last quarter of 2024 has seen several interesting launches. Here is a quick recap:

Gevulot transitioned into ZkCloud, moving to the back as the “Labs” entity behind ZkCloud, the first universal proving infrastructure for ZK. Launched in early 2023, Gevulot has been working consistently on making ZK proving cheaper and easier. We published our protocol design in 2023 and launched the first version of the network in March 2024, achieving 2M+ proofs generated and 5M+ verifications. In December, we launched Firestarter, our scalable, production-ready network, live now and generating proofs.

Under the hood, Firestarter is an end-to-end implementation of Gevulot’s ZkCloud mainnet, just running in a permissioned fashion: Gevulot Labs is running all validators for now, while proving compute is already decentralized, and workloads being allocated through random selection. Firestarter is designed to scale to thousands of prover nodes handling both CPU and GPU workloads, as well as incorporate specialized hardware as that becomes available. Users can generate proofs using one of the pre-deployed provers, such as Risc0, SP1, Aztec, ZKsync, Starkware, Scroll or Polygon, or by deploying their own.

Nexus launched the beta release of the Nexus Network in early October. The network’s goal was to aggregate the computing power of various device types, ranging from user devices to GPU farms. Participants could join by connecting through a desktop or mobile browser, or via a CLI tool, to contribute computing resources. In early December, the team also launched a testnet that also allowed users to contribute proof cycles to the network. Over the coming months, the team will be rolling out a series of testnets to explore how the Nexus zkVM and the network can function at scale.

ZEROBASE launched its ZK prover network in October 2024. The network aims to provide privacy through TEEs and decentralized proof generation for various use cases, with a focus on applications implementing ZK. The protocol employs a hub-based architecture to manage and distribute network nodes and ensure fault tolerance. Hubs are centralized sub-sets of nodes where each node communicates only with its assigned hub, however, additional hubs can be created as the network scales.

Lagrange launched its prover network called “The Infinite Proving Layer” in December. The protocol is built as an AVS on Eigenlayer, utilizing restaked assets as economic security (similar to Fermah). Workload allocation in Lagrange’s prover network is based on DARA, a double-auction mechanism published by the team in October. In DARA, bidders (proof requesters) and distributors (proof providers) submit private bids. At the core of the mechanism lies a novel dual-ranking system for both parties. The mechanism ensures the best-ranked bidders and distributors are matched in a way that maximizes welfare and truthfulness, however, it does not fully address the risk of centralization, because rich proving entities could still become dominant through prover undercutting after having found out the lowest accepted bid by submitting incrementally lower bids over multiple auction rounds. Proof providers willing to sacrifice profitability for dominance in the network could use this to increase their ranking.

Succinct released its whitepaper for the Succinct Network, the prover network supporting proof generation for SP1, the team’s in-house zkVM. The network will be deployed as a set of smart contracts on Ethereum, combined with off-chain participants that manage prover selection and request matching. Workload distribution will happen through an all-pay auction, where all bidders pay their bid, regardless of winning the auction. In this mechanism, prover nodes submit bids for the right to prove a request, and their bid does not determine the fees they earn. In other words, the bids are interpreted as the amount a prover is willing to pay to receive the fee from the requester and complete the proof. The winning provers are selected with probability proportional to their bid within the sum of all bids: on the one hand, this means that every new bid decreases the selection probability per dollar, on the other hand, it allows wealthy entities to increase their probability for winning the auction by submitting multiple bids and thus directly influencing their proportion in the total bids.

The above shows that protocols might be taking very different approaches when it comes to key protocol design elements such as workload allocation, a topic we have analyzed more thoroughly in our previous report.

Now, we are going to explore the question of economic security for prover networks and marketplaces. Proof generation is a one-of-a-kind task: it is compute-heavy, and in that sense, it resembles Proof of Work, but it might also require economic security through staking, which is characteristic of PoS networks. We’ll dive into what design elements (or some combination of theirs) could become part of the security guarantees behind proof generation.

Economic security in the context of proof generation

Proof-mining vs. Bitcoin-mining

When discussing the topic of economic security behind proving, let’s start by exploring Bitcoin mining to see what we can learn and whether there is something to be applied for proof generation, often also referred to as proof mining.

Both proof-mining and Bitcoin-mining require substantial computational resources, however, they serve fundamentally different purposes.

Bitcoin mining uses Proof of Work (PoW) to secure the network and achieve consensus, with miners competing to solve cryptographic puzzles.

In contrast, proof-mining generates zero-knowledge or validity proofs to make data and computation verifiable without re-execution.

There is a clear parallel though: in both cases, participating in mining involves a significant economic commitment in the form of hardware costs.

On the other hand, the two economic models differ significantly: Bitcoin mining's competitive nature, where only the winning (fastest) miner receives rewards, and the redundant computation involved, is integral to network security.

The competition involved in Bitcoin mining can be compared to "proof racing" where all provers compete to generate the proof but only the fastest one gets rewarded. This mechanism is very inefficient for proof generation, as it creates excessive wasted computation, conflicting with the goal of minimizing proving costs.

This suggests that designing secure, efficient prover networks requires alternative mechanisms. However, in what form they should come, is non-trivial.

The common answer: staking

To spare the wasted computation of proof racing and to ensure reliability and performance, economic security through staking (or the form of a bond) is the common answer. Let’s dive deeper to understand what purpose it serves, and whether there are alternatives.

Sybil resistance: Forcing prover nodes to lock tokens creates a cost to participate, preventing attackers from easily spawning unlimited identities (Sybils). The size of the required stake must exceed the potential profit from acting maliciously.

Let’s take note though, that the costly hardware required for proving could cover this: at sufficiently high HW utilization it becomes impossible to back multiple Sybils with the same hardware.

Economic security: Staked tokens act as collateral that can be slashed if a prover delivers invalid proofs. It encourages producing valid proofs efficiently to earn rewards while discouraging dishonest behavior.

We note that for permissionless and universal prover networks, like ZkCloud, where the users can deploy their own prover binary and get proofs generated, slashing is not trivial: in case of a malicious binary that never outputs a proof, the prover nodes cannot be slashed.

Liveness and availability: Staking can ensure prover availability, guaranteeing that proofs are generated on time, which is crucial for network operations like finality in ZK-rollups. In case of non-delivery in an auction-based proof market, the proof requester might need to restart the auctioning process, which adds latency, and complexity to source a proof.

However, there are also some counter-arguments against staking:

Higher entry barrier: If the hardware cost and operational overhead are already high, staking might mean too high an economic burden, potentially increasing the entry barrier, and centralizing the network to wealthy entities that can afford both hardware and stake.

Opportunity cost: There is an opportunity cost to the staked tokens, which needs to be considered. In the competitive space of proving, where there is a race to the bottom for proving costs, prover economics and profitability need to account for this.

What about restaked economic security?

More and more protocols are building their prover networks or marketplaces as AVS on EigenLayer, the first protocol to introduce the concept of restaking where staked ETH or Liquid Staking Tokens (LSTs) can be leveraged to secure additional services beyond the Ethereum itself. Building a proof market or prover network as an AVS comes with multiple advantages, such as lower bootstrapping costs and faster go-to-market, but it comes with risks that must be considered.

The tension between individual rational behavior and system security: Operators are incentivized to maximize returns by restaking across multiple AVS services. However, each additional restaking commitment dilutes the actual economic security behind each service. This creates a "tragedy of the commons" situation where individual optimization may lead to systemic risks.

In simple words, if 1000 ETH is restaked across 5 AVS protocols, each service isn't backed by 1000 ETH of security. They share 1000 ETH-worth of economic security, and in case of a critical failure or attack, especially if multiple protocols are affected, the slashing of shared security can have cascading effects. And the correlation risk increases with each additional AVS service.

Let’s do some calculations:

As per their dashboard on 6 Feb 2025, there are a total of 35 AVSs active on Eigenlayer, and the total TVL in Eigenlayer is $13.05B.

To calculate how many AVSs the same restaked assets are backing, we need to sum up the individual TVLs of all AVSs and divide it by Eigenlayer’s TVL. The formula is the following:

Average AVSs per dollar = Total TVL across all AVSs / Total Eigenlayer TVL

This means that on average 11.3 AVSs are backed by the same restaked USD value.

Prover networks and marketplaces using restaked assets as economic security should consider the above when designing their architecture and implement risk mitigation measures accordingly.

Are there alternatives to (re)staking?

Let’s look at some viable alternatives to economic security:

Reputation systems: Instead of staking, a reputation system where provers are rated based on their past performance, timeliness, and reliability could incentivize honest behavior. Nodes with poor performance could be deprioritized or excluded from future task allocations.

Performance- and reputation-based rewards: A system where rewards are dominantly performance- and reputation-based (the two are essentially the same) can mimic the economic security of Bitcoin mining. Provers earn rewards based on how reliably and fast they generate proofs, and risk losing potential revenue and accumulated reputation if they perform poorly.

Cost of non-delivery: Similar to Bitcoin's PoW where miners waste energy on incorrect guesses, provers can face penalties for submitting invalid proofs or failing to deliver on time, where the penalty could be in the form of losing current and future revenue, for instance, through excluding the prover node from task allocation for a certain amount of time, or kicking it out of the network.

Proof of capacity and availability: Prover nodes could be mandated to complete proving workloads in times when their capacity is not filled up with actual proving jobs to prove that they are consistently available and capable of generating proofs. Failing to complete these workloads could result in forced removal from the active prover set. This could efficiently decrease the risk of Sybils where multiple entities use the same hardware for proof generation.

Extended activation period and capacity verification: To avoid the fast re-joining of nodes that were kicked out, an extended entry period could be implemented during which prover nodes need to constantly complete proving tasks to verify their hardware capacity. Paired with a performance-based reward system, the cost of malicious behavior may already be quite high.

While more research is needed to explore the optimal architecture design, through combining the above design elements, one could build an efficient mechanism that mitigates Sybils in the network, force-removes non-delivering prover nodes, and ensures liveness and availability, while providing sufficient security guarantees, without the elevated entry barrier and opportunity cost that staking introduces to prover networks.

Closing thoughts

The year 2024 has marked a significant evolution in the proving infrastructure landscape, with projects moving beyond theoretical frameworks to practical implementations. There has been a clear trend in the industry toward decentralization of proving infrastructure, exemplified by Aztec, ZKsync, Taiko, Scroll, and others.

While economic security through staking or restaking remains the dominant approach among decentralized prover networks, the financial models behind proof generation remain an important area of future exploration to balance security, decentralization, and accessibility. As the industry continues to mature, finding the right balance between robust security guarantees and accessible participation will be crucial for achieving true decentralization in proof generation.

Looking at the increasing pace of innovation in the overall ZK landscape, we believe the industry is fast approaching a tipping point in both adoption, as well as performance, scalability, and decentralization.

Let’s make 2025 the year of ZK.

Disclaimer:

The proving landscape is evolving day by day. If you feel we missed out on some important protocols or developments, or find any inaccuracies, please get in touch with Norbert from the Gevulot team, and we can make the necessary changes.

___

About ZkCloud:

ZkCloud, built by Gevulot, is the first universal proving infrastructure for ZK. Generate ZK proofs for any proof system at a fraction of the cost. Fast, cheap, and decentralized.

Learn more about ZkCloud:

Website | Docs | GitHub | Blog | X (Twitter) | Galxe Campaign | Telegram | Discord